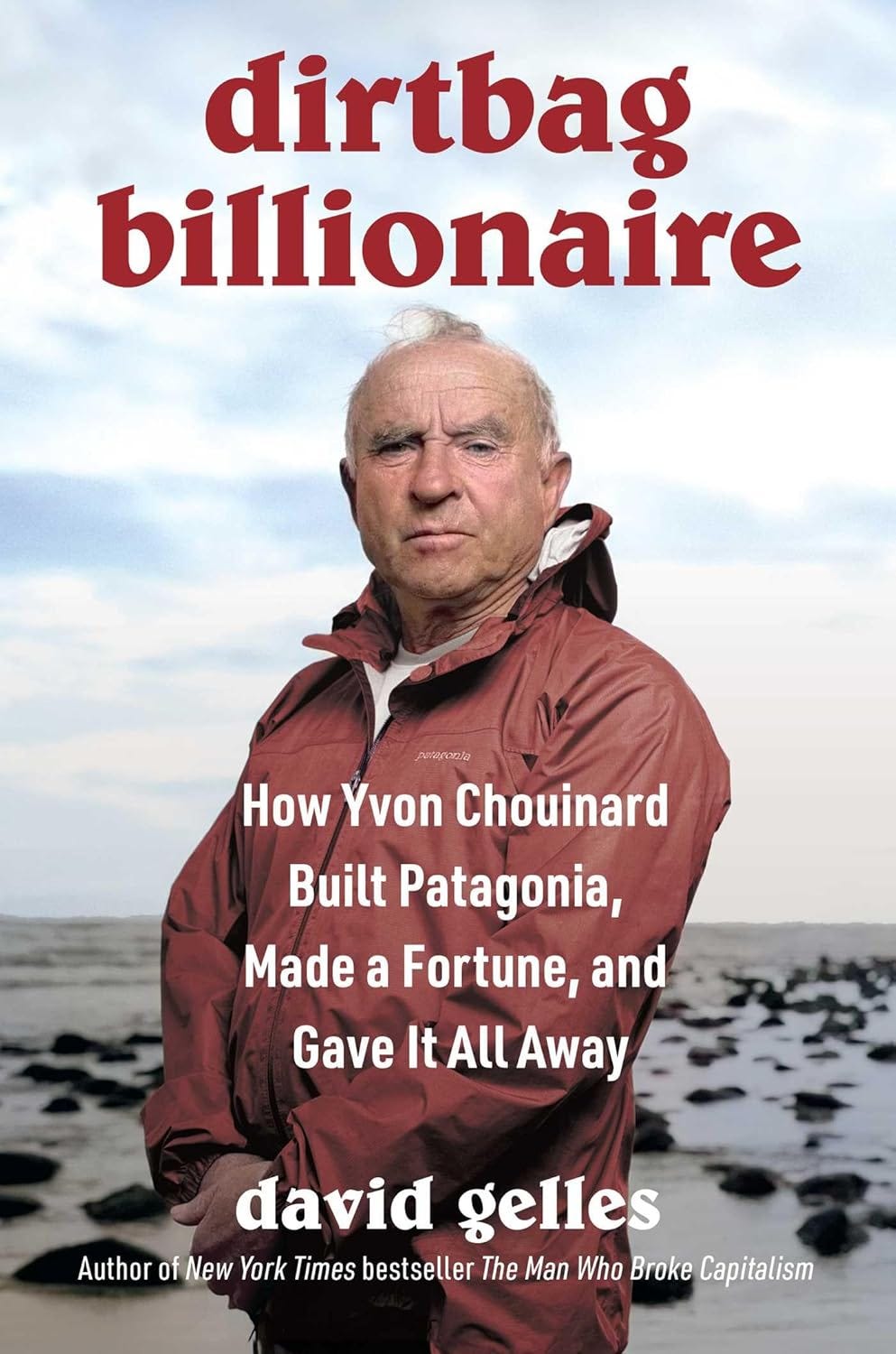

Dirtbag Billionaire

How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave It All Away

Gelles, David. Dirtbag Billionaire: How Yvon Chouinard Built Patagonia, Made a Fortune, and Gave it All Away. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2025.

Overview

The life and work of Yvon Chouinard is a great story that, for whatever reason, has been sitting just below the cultural radar for most of us. From the jump—indeed from the title, Dirtbag Billionaire—this is a story about stunning contradictions. How can someone be both a grubby outdoorsman and fantastically wealthy? How can a big company participate in global capitalism and be sustainable? How can someone who despises businessmen and seems to want to spend as little time working as possible become an iconic businessman? Somehow Gelles’s book pulls all those threads together in a way that makes sense.

About the Author

David Gelles was the right guy, in the right place, at the right point in his career to tell this story. Gelles is a business reporter for the New York Times whose first book was on mindfulness at work and whose second book was a scathing takedown of Jack Welch’s approach to American capitalism. This book on Chouinard is almost a perfect counterpoint to the Welch book. Where Welch focused on making GE as big as possible no matter how much damage was caused along the way, Chouinard seemed to grow Patagonia somewhat reluctantly, always with a desire to build something of enduring value and leveraging the company’s position to have the maximum possible positive impact on the planet. Having read both books, I can feel how Gelles’ critique of Welch fuels his desire to shine a light on the positive things Patagonia is doing (or at least trying to do).

“Top Ten”

I listened to Dirtbag Billionaire on audiobook, which is an excellent version read by the author. So I didn’t actually read the text on the page and underline sections, etc. This summary is meant to communicate what I consider the top ten most interesting and useful takeaways, based on memory and shorthand notes. My hope is that this summary convinces you that this is one of the great business stories of our era, and you buy the book or audiobook and review Gelles’ work in full. It’s worth it.

1. Dirtbag Ethos

It’s impossible to understand the story of Yvon Chouinard (or Patagonia) without picturing him in your imagination as a “dirtbag” climber. In the 1960s, climbing as we understand it today was in its infancy. You have a first wave of modern climbers who are fanatics, living in their cars or camping throughout the climbing season, surviving on very little money and food, and establishing the first set of routes on mountains that are now famous, like El Capitan at Yosemite. Yvon was one of these people. Though he grew up from age eight in Southern California, he was born to a French Canadian family in the backwoods of Maine. His dream was to be a fur trapper and, throughout his life, he exudes an energy that seems more comfortable outside than inside. When he talks about the lessons from his early life, he muses: Nature is to be revered. Conventional wisdom is to be ignored. The modern world is not to be trusted. An interesting side note is that a couple of other dirtbag climbers of this same era grew into successful businessmen in the outdoor apparel industry, most notably Chouinard’s very close friend Doug Tompkins, who founded North Face and later Esprit before becoming a leading environmentalist.

2. Not an Inventor, but a Consummate Innovator

In the early days, climbers used steel spikes called “pitons” that were driven into cracks in the rock face to secure ropes. The pitons widely available at the time Chouinard took up climbing were made in Europe out of soft steel and were pretty cheap, costing about $0.15 each. Chouinard found these were not durable enough for extensive reuse, and if you attempted a very long climb, you would need an enormous quantity. So he innovated, making new pitons himself out of hard steel with a blacksmith forge and anvil. His cost 10x as much ($1.50 each) but could be reused forever and therefore opened the path to longer climbs. This is characteristic of Chouinard throughout his career: he didn’t invent new things but rather sought to make whatever he touched better.

3. Blacksmith and Surfer

Chouinard settled into a rhythm where he would hit the mountains during climbing season, then migrate to the beach for the winter. He rented a little shack in Ventura and set up a blacksmith shop, where he’d crank out pitons. When the surf came up, he’d abandon his forge and go surfing. When climbing season was back on, he’d load up his car with his products, then sell them out of his trunk to climbers to support himself through the climbing season. This lifestyle of living like a bum, surfing half the year, then climbing half the year, seems like an eminently wonderful way to spend one’s early 20s. One wonders why this isn’t presented as a legit option for America’s youth right now? It is basically lifestyle design vis-à-vis Tim Ferriss’s 4-Hour Workweek. You can feel a sense of independence and freedom that took root in Chouinard’s soul and gave him the courage and license to ignore corporate conventions when building his companies. He founded a climbing equipment company, Chouinard Equipment, Ltd., several years before founding his apparel company, Patagonia.

4. Quality. Quality. Quality.

Chouinard’s North Star is: whatever you are going to do, strive to be the best in the world at it. I’ve heard a lot of other people say this, but I’ve never seen someone DO IT with such direct sincerity and purity as Chouinard. His pitons were the best in the world. When he started making outdoor clothing, he was obsessed with making it the best outdoor clothing in the world. He firmly believed people would pay premium prices for quality. I saw him give an interview the year in 2025 and he said if he started over right now, he’d focus on food. “I’d make a restaurant that only sold beans and rice. It would be the best beans and rice restaurant in the world.” I absolutely believe he would achieve this.

5. The Company is Not the Product

Chouinard has maintained a lifelong suspicion of businessmen, whom he often derides as sleazeballs. The concept that the product of one’s labor is the “company” or, worse yet, “stock” is, for Chouinard, offensive. Instead, he believed the products themselves should be the focus. Concentrate your primary energy on making that product (or service) the tip of the wedge, then allow everything else to fall into place behind that. It’s a powerful vision, and when he describes it, you can feel him standing against the tide of the kind of advanced American capitalism represented by people like Jack Welch. One stinging contradiction here—something that Chouinard points out all the time—is that quality does not scale. Here is a great and rare youtube video of Chouinard in action. Worth watching if you are in the mood for your soul to grow.

6. Breastfeeding Mothers Story

Since the beginning, Patagonia was built by hiring friends, then friends of friends. In the early days, the company was disproportionately female, leading to the establishment of one of the first on-site daycares in America as well as a generous policy for nursing mothers. If one of the female Patagonia corporate employees was traveling on business while nursing, the company would pay to send an assistant to handle the child while the mother was in her meeting. This seems extremely enlightened, but at the same time, one gets the sense reading Gelles’s book that working at Patagonia wasn’t an endless barrage of frills. Sort of the opposite. The Patagonia employees never got stock in the company and didn’t seem to share significantly in the huge profits in ways you might expect. Also, there was one point where Patagonia tried to scale too fast, then hit a rough patch and almost crashed as a company. The large round of layoffs at that moment was the darkest day for Chouinard as a business leader. The company also churned through CEOs, with the notable exception of Kristine McDivitt Tompkins, who ran the company very effectively for 20 years. You get the sense that when you worked for Patagonia, you had a job anchored in deep purpose. At first, that purpose was craft of great products and love of the outdoors, but then it steadily extended to care for the planet.

7. Endless Interrogation of the Supply Chain

I did a Google image search of the Patagonia office and there was a sign on the wall that said, “It’s broke, fix it.” Gelles spills a lot of ink recounting Patagonia’s quest to improve the quality of the supply chain. The poster child for this part of the story is cotton. Of all the crops in America, cotton is among those most heavily reliant on pesticides. When Chouinard visited the industrial cotton farms, he was so appalled that he said they’d either find an organic source of cotton or simply stop using it (at a time when something like 30% of the company’s sales came from cotton products). They innovated and got the organic cotton, going so far as to co-sign loans for organic cotton farmers who could provide material to Patagonia. Similarly, they’ve found ways to make nearly cradle-to-cradle synthetics and non-toxic dyes. Then they moved on to labor practices. The more you dig into the supply chain, the more problems you uncover. Patagonia just seems to keep trying, standing against the tide of apathy. Commendable and still far from perfect. They are still working at improving the supply chain right now.

8. Gave Company Away to the Planet

When Chouinard got named to the Forbes “billionaire list,” he was deeply disturbed. He is a cool enough guy, but fundamentally a crusty, cantankerous old bastard who still lives in a simple house and uses old dishes. He never set out to be a rich businessman, and the label “billionaire” repulsed him. At the same time, he didn’t trust the people in his company enough to divide up the stock. His children didn’t want to take over the company. So Chouinard convened a team to figure out a tenable long-term solution. What they ended up with was establishing a benefit trust, similar to what a very rich person will set up for a pet that outlives them. Usually this is a minor part of an estate, but it’s designed to be very tightly governed and hard to circumvent. Chouinard basically put all Patagonia shares into this form of trust, then named the beneficiary planet Earth. Therefore, in perpetuity, the vast majority of proceeds from Patagonia will go toward environmental causes.

9. Tercentenarian Club

Chouinard is very focused on long-term thinking. How will you build a great business that can last long into the future? His dream is that at some point Patagonia will belong to the Tercentenarian Club, where member companies have been going for at least 300 years. One of his favorite businesses in the world is a little shop in Kyoto that just sells pickled plums, but they have been selling the same pickled plums in the same place for 500 years. They still use an abacus to ring customers up. This is the stuff Chouinard dreams about.

10. What’s the Catch?

The question that I am left with at the end of this book is: how did Chouinard and Patagonia enjoy so much growth over time? For any company to achieve the year-on-year growth Patagonia enjoyed is almost too easy. The best guess I have is that four factors were active in their success:

First, Timing. Starting an outdoor apparel business in the 1960s would be like starting one of the major social media companies in the 2000s, where a handful of early successful players are rewarded with huge new markets.

Second, Innovation and Quality. Patagonia had the North Star of performance, and they constantly focused on improvements—inventing new materials, ratcheting up the quality of the supply chain, raising the bar on design. This led to unparalleled quality that made the brand premium for two groups: outdoor enthusiasts who paid more because they relied on the gear, and yuppies who could afford it.

Third, Culture. This flowed from Chouinard’s own character but grew into its own thing too. Chouinard himself wrote a book on his business philosophy called Let My People Go Surfing. The headline cultural value was that when the surf was up, Patagonia employees who were not working on critical projects could drop what they were doing and go surfing. Building a company out of outdoor enthusiasts who are naturally environmentalists all feels like a reinforcing feedback loop.

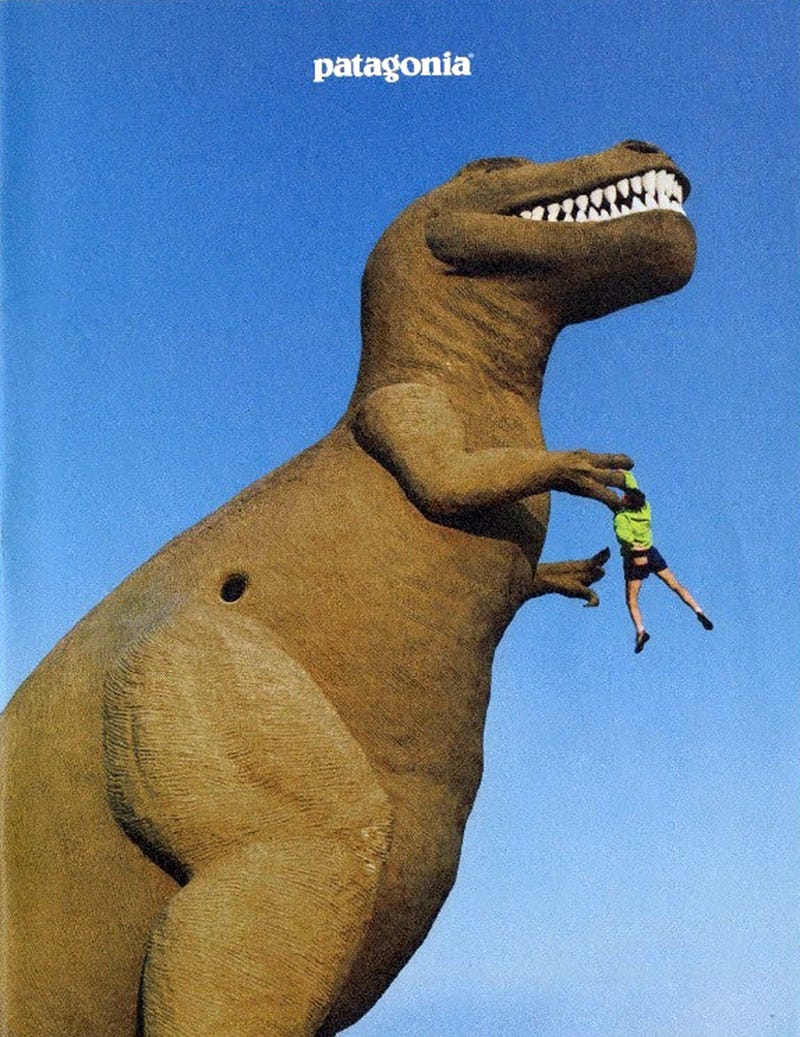

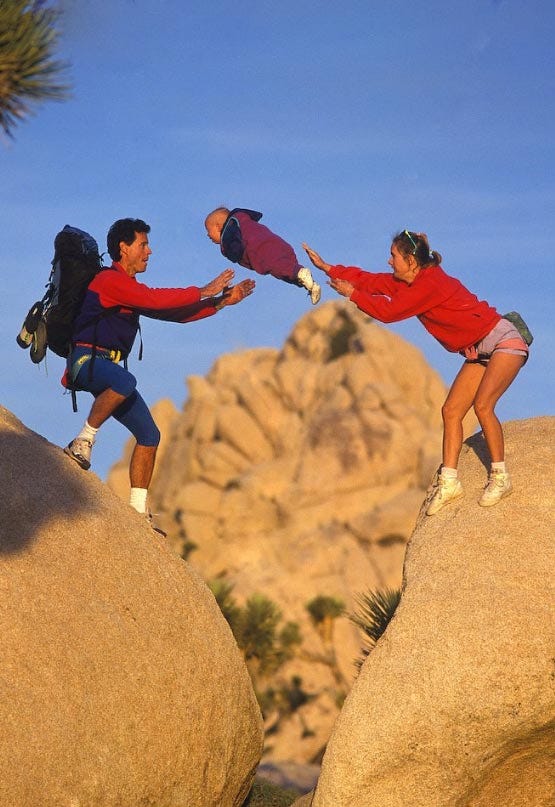

Fourth, Marketing. Over the years, I’ve grown to believe two contradictory things at the same time: a) companies can grow like crazy while spending basically $0 on marketing (e.g., Tesla), and b) really great marketing that is an expression of the soul of a brand can contribute mightily to growth (e.g., Apple). Patagonia is a great example of the latter. They struck gold when they asked outdoor enthusiasts to send them pictures of their gear in action that they could use in their catalog. The T-Rex and Baby Toss are all you need to see to know what I’m talking about.

So what? Of all the books I could read, why this?

I think Gelles has told a story of an American business and capitalism that is very uplifting. At a time where we have a lot of reasons to be cynical, the story of Chouinard in particular, and Patagonia generally, is inspiring. We are not the victims or hostages of the modern world order. We can participate in building great companies that help create the kind of world we want to live in and leave behind.